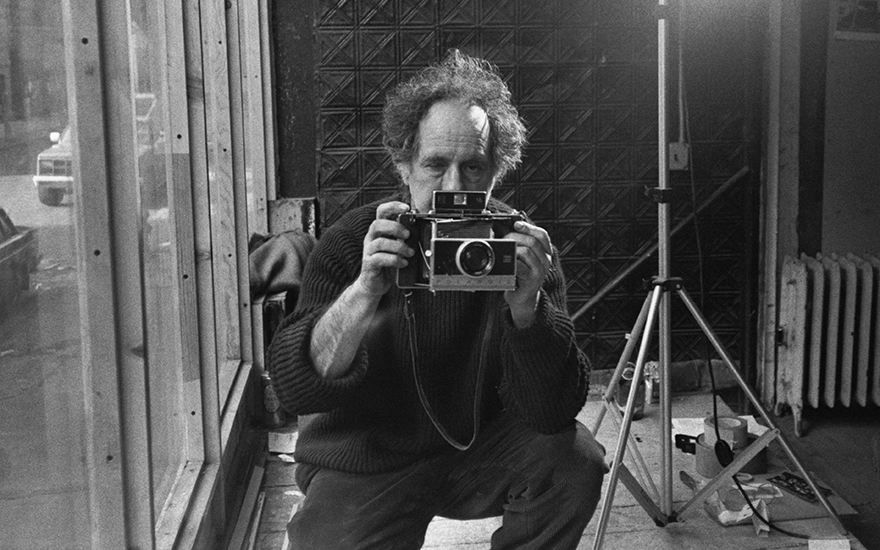

One of the most cited figures in twentieth-century photography, Frank’s contribution to the post-war era is his revelatory book The Americans, which was not only a seminal work of photography but a prickly social document that challenged the rosy picture of American life widely accepted during the Eisenhower years. Although Frank’s career has spanned more than 50 years, he has always worked, to some extent, in the long shadow cast by The Americans. Frank expressed his frustration at the legendary status of his early work as follows: ”I wished my photographs (the old ones) would move – or talk – to be a little more alive”; and much of his subsequent work has been more of the same: varied, experimental and multimedia, incorporating film, video, text, poetry and performance. A peer of Henri Cartier-Bresson, who enjoys a similarly legendary status with photographs that capture the mood of the street and the alienation of the individual in society, Frank’s philosophy is in fact diametrically opposed to that of the French photographer. There is no such thing as a ‘decisive’ moment,” Frank famously said. “You have to create it. I have to do everything necessary for it to appear in my viewfinder” (Conversations in Vermont [film] quoted in Bild fur Bild Cinema, Zurich, 1984). Most of his work, apart from The Americans, is in fact autobiographical, even confessional.

Robert Frank was born on 9 November 1924 in Zurich, Switzerland, the son of Hermann Frank and Rosa Zucker, a Jewish couple. He attended primary and secondary school in Zurich and, after leaving school, was apprenticed to the graphic designer and photographer Hermann Segesser from 1941 to 1942.

Although Jews were being exterminated throughout Europe, the Franks were able to live their lives relatively undisturbed in the safety of neutral Switzerland. As a German immigrant, however, Hermann Frank and his sons Robert and Manfred were forced to apply for Swiss citizenship in 1941.

Robert Frank was finally granted official Swiss citizenship in 1945. During this period of uncertainty, he had continued to study photography, working as a still photographer on a film and in the film and photography studio of Michael Wolgensinger.

Wolgensinger had studied with Hans Finsler, who had trained at the Bauhaus, and he taught Frank about large-format cameras and taught him classical and experimental techniques by example.

Frank was briefly an assistant to a photographer in Geneva and was impressed by the work of the leading Swiss photographer of the time, Jakob Tuggener, who documented the streets, architecture and social life of Switzerland in a straightforward and unsentimental way.

After military training in 1945, Frank moved to Basel to work at the Hermann Eidenbenz studio, a graphic design firm, where he produced his first book, a unique volume of original prints called 40 Fotos (street photographs taken with a 6×6 Rolleiflex), and travelled with his family to Paris and Milan. Frank’s desire, however, was to leave Switzerland and go to America, which he did in 1947, arriving in New York in February of that year. He found employment as a junior photographer at Harper’s Bazaar magazine under the tutelage of the legendary art director Alexey Brodovitch. This association was short-lived, however, and by the autumn he had quit to work as a freelance photographer, doing assignments including fashion shoots for a variety of publications, including magazines and newspapers such as Life, Look and The New York Times. Frank bought a Leica 35mm rangefinder and embarked on a series of trips, particularly to Peru and Bolivia, which he compiled into a book of original prints. It was also in the late 1940s that he met his future wife, Mary Lockspeiser, whom he married in 1950. Mary Frank, from whom Robert separated in 1969, went on to become a well-known artist, working mainly in ceramics. The year 1950 marked his introduction as an exhibiting photographer when he was included in the landmark group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, 51 American Photographers.

After the birth of their first child, Pablo, in 1951, the Frank family moved to Paris. Frank travelled to the United Kingdom, where he photographed in London and later in Wales (1953). In England, Frank came to know and admire the work of Bill Brandt and, somewhat under his aesthetic influence, made a series of photographs of miners.

These early works from London and Wales were reissued in book form in 2003. Back in Paris in 1952, he met Edward Steichen, who was in Europe researching photographers for exhibitions at MoMA, including The Family of Man, mounted in 1955. Frank travelled extensively during this period, returning to New York in 1953, where he became friends with Walker Evans, for whom he later worked as an assistant. Evans’s book, American Photographs, also had a major influence on Frank’s rapidly developing ideas about the sequencing of photographs. His second child, Andrea, was born in 1954, and he met the poet Allen Ginsberg, who was to become an important influence and collaborator. He also took his first photograph for what would become The Americans at a Fourth of July event in upstate New York (Fourth of July-Jay, New York). Frank’s restless desire to travel was facilitated in 1955 when he was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, the first European to receive such a grant. With this fellowship and its renewal in 1956, he crisscrossed the United States, photographing in New Jersey, Chicago, Detroit, North and South Carolina, Hollywood, the western states of Montana, Idaho, Nevada and Nebraska, the southwest in Arizona and New Mexico, especially along Route 66, then the main artery across the nation, along the Mississippi River in the Deep South, and Texas. After photographing Dwight D. Eisenhower’s inauguration for his second term in 1957, Frank selected and printed the works for the book he had in mind.

While trying to find a publisher, he worked on his first film, a 16mm short shot in Florida with Beat writer Jack Kerouac, whom he’d asked to write an introduction for his book. Later commentators note that Frank was responding to the massive project on which he had collaborated (and in which he was included, both with his own work and in a portrait of him and his wife by Louis Fauer), Steichen’s The Family of Man. Kerouac’s introduction is diametrically opposed to the humanistic, often romantically idealistic language of Carl Sandburg’s introduction to Family. Frank shared with Kerouac, whom he’d met in New York, a more realistic – some might even say cynical – view of post-war America and its social structures, including rampant segregation, the huge gap between rich and poor, the dark fears aroused by the Cold War and the constant threat of nuclear holocaust, the alienation of youth exemplified by the emerging ‘beatnik’ culture that Kerouac so brilliantly chronicled. That he couldn’t find an American publisher was not entirely unexpected, frustrating though it was. That would change with a trip back to Paris and the embrace of the project by the visionary publisher Robert Delpire. First published in 1958, the book has never been out of print. Opening with a now classic image of two figures standing at the windows of an ordinary brick building, the American flag waving at the top centre of the image (Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey), 82 images follow, showing a panorama of American life in dark, dense tonalities. Politicians in top hats contrast with African Americans in fedoras and straw boats attending a funeral (Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina). A glamorous Hollywood starlet (Movie Premiere – Hollywood) contrasts with a Hollywood counter waitress (Ranch Market – Hollywood).

The works are exquisitely selected and presented, forming rhythms and meanings that weave their way through the book. The ‘big themes’ of The Family of Man are also presented, but they speak quietly, without the emotional staging of that project. Death is poignantly juxtaposed with the joy of life through the juxtaposition of an image of an exuberantly smiling African American woman sitting in a chair against the setting sun in a weedy field (Beaufort, South Carolina) and a view of a funeral on the next page showing an elderly African American in his coffin as formally dressed men pass respectfully by (Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina). The ‘exotic’ is found in a cowboy leaning against a garbage can in an urban setting (Rodeo – New York City), the personal in the book’s final image of Frank’s own car, with his wife and child sleeping inside (U.S. 90, en route to Del Rio, Texas). But the individual images stand up as works of art: among the most famous are a black nurse holding a baby so preternaturally white it seems to glow (Charleston, South Carolina) and a tuba player at a political rally, his face completely obscured by the giant circle of the tuba’s horn (Political Rally-Chicago).

Although the process of shooting the classic images that make up The Americans was a solitary, peripatetic activity, Frank’s more common process is one of collaboration. His well-known 16mm film Pull My Daisy (1959) was made with the New York painter Alfred Leslie and is a free interpretation of an act from Jack Kerouac’s play The Beat Generation.

Frank went on to make more than 20 films, including Me and My Brother (1965-1968), Cocksucker Blues (1972) with Mick Jagger and Keith Richard of The Rolling Stones, and This Song for Jack (1985) with Beat poets and writers Gregory Caruso, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, dedicated to Jack Kerouac.

Frank also produced the music videos Run for New Order (1989) and Summer Cannibals for Patti Smith (1996).

His work after The American is filled with family, friends and places that reflect the fabric of his life. During the 1960s, he concentrated primarily on making films, although he began to have some success with his photography: his first solo museum exhibition was at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1961, and the George Eastman House purchased 25 images from The Americans in 1965. The photographs that made up his next publication, The Lines of My Hand, began to accumulate. Published in 1972, the book looks inward, at Frank’s own life and what it means to be an artist.

In 1970, with his marriage to Mary over, Frank had become involved with the artist June Leaf, and together they bought a property in the desolate, often extreme climate of Mabou, Nova Scotia, where they built a studio and lived part of the year, and which would become the setting and subject of many photographs. The 1970s were full of personal difficulties for the photographer; his daughter Andrea, only 20, died in a plane crash in Guatemala in 1974. His close friend and frequent collaborator on films, Daniel Seymour, disappeared and was presumed dead. His father died in 1976. His son Pablo, who would eventually commit suicide, was increasingly troubled by mental illness, and Frank unflinchingly confronted these tragedies with his camera, often in montaged sequences of snapshot-like images that are difficult to read because they are fractured, shot at extreme angles, and inscribed with texts, some written into the film’s emulsion. Rather than the fluid narrative of The Americans, the works in The Lines of My Hand are disjointed and resist easy interpretation. Many are clearly expressions of grief and are often painful to engage with, such as Monument for my Daughter Andrea, 21 April 1954/December 28, 1974, which consists of Polaroids presented on a photo album page, or Sick of Goodby’s, 1978.

In 1990, on the occasion of a major retrospective organised by the National Gallery of Art, America’s most prestigious museum, the Robert Frank Collection was founded. Consisting of negatives, contact sheets, works and exhibition prints, it is a fitting tribute to the Swiss-born artist who helped reveal America to itself. But Frank’s work is best summed up by Hold Still – Keep Moving (1989), the title of his retrospective at the Museum Folkwang in Essen in 2000.

A photograph is taken from the flow of life; it holds life still, but all the photographer, or the viewer, can do is keep moving.